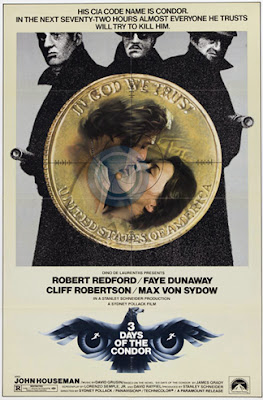

The question, "How fictitious is fiction," puts me in mind of an excellent film released in 1975 by Sidney Pollack – 3 Days Of The Condor. Joe Turner (Robert Redford) is a CIA employee (Condor is his code name) who works in a clandestine office in New York City. He reads books, newspapers, and magazines from around the world, looking for "hidden meanings and new ideas". As part of his duties, Turner files a report to CIA headquarters on a low-quality thriller novel his office has been reading, pointing out strange plot elements therein, and the unusual assortment of languages into which the book has been translated. One day Joe returns from buying a sandwich and finds everyone in his office has been shot dead. Following his training he runs into hiding but soon realises he can trust nobody - least of all his employers.

I loved this film and found it an intriguing subject. Just like the book in the film, however, the film itself seemed to me like it might have been based on truth. The danger to the CIA, the US government and other unknown powers, was that the reading public would spot the fact that the story had a little too much authenticity – that what was written was very close to real life circumstances, and that they would put two and two together. They could not, of course, allow this to happen. So how far does that seem from reality, eh?

The dictionary provides several definitions of fiction. I find them particularly interesting:

1.

a. An imaginative creation or a pretence that does not represent actuality but has been invented.

b. The act of inventing such a creation or pretence.

2. A lie.

3.

a. A literary work whose content is produced by the imagination and is not necessarily based on fact.

b. The category of literature comprising works of this kind, including novels and short stories.

4. Law Something untrue that is intentionally represented as true by the narrator.

I especially like number 2. A Lie. All my own writing is lies. An imaginative creation may sound more literary perhaps, but I prefer "lies".

image courtesy of www.overtheretohere by John Burningham

But fiction needs to be more than lies. It is in the nature of fiction writing, that what is written seems believable, is it not? Lies are all very well, but we need believable lies. Even with fantasy writing or with science fiction, if the job is done well, the reader's disbelief is suspended. Something that may be far fetched still has a sense of authenticity. When it does not, the reader is dissatisfied. So how does the writer achieve this?

I think it is generally true to say that good fiction writers have highly developed observational skills. They notice how people behave and how others respond to their behaviour. They will usually have a wide experience of people, cultures and circumstances. These skills and their life experiences are then married to a literary ability to describe characters and situations in words (including in film scripts). Both elements are required to achieve success. So the fiction writer is a repository for a mass of memories about people and circumstances; of life stories and intriguing events. All things that are filed away in their mental library for future use as fiction. Why are we surprised, therefore, when people or events found written into fiction, bear a strong resemblance to people or events we know? Why accuse the writer of presenting fact as fiction? Must we fiction writers tweak things to ensure that they do not seem too authentic, for fear of such accusations?

image courtesy of www.numera.com

In my own writing, I have experienced exactly this phenomenon. People say (very flatteringly) that my writing has an overwhelming sense of authenticity. Not just the stories, but the detail. Particularly the characters, they say. The descriptions of my characters, what they do, what people say and most importantly how they say it, give the reader the sense that I am describing a real person and a real event. "Surely," I say, "all good fiction should do this?"

"Fiction my arse, I know that Newsreader"

Since the publication of my first book, The Pimlico Tapes, my publisher has received over a hundred accusations from people who claim that the characters (in this case the patients of a therapist) are in fact wholly and completely them, or someone they know. Only the name has been changed, they say. I call it "The Condor Effect." What makes this especially problematic, is that some of these patients are famous and therefore wealthy people with a taste for instant litigation, especially where their private lives are concerned and especially when it concerns sex. Their claims are hard to prove but it does not stop them trying, and that can be tiresome as well as expensive. Why do these people find it so hard to believe that their particular issues (the one's they have gone to a therapist about) are not unique to them. This is how palm readers and clairvoyants manage to dupe people. "You met a dark haired man recently and something he said made you nervous of him." "Someone in your family told you something that hurt you." Almost everybody will identify with these statements. It does not make the palm reader a gifted seer or a genius! The skill of the fiction writer is to conjure up something that people will immediately identify with. Something perhaps that they will feel is personal to them. Yes the individual components of what is described will come from the writers real life memories, but few would write them down exactly as they had happened in real life. In most cases it would not fit the story anyway. But I think what I have been accused of is actually the opposite of the legal dictionary definition 4. above:

Law Something untrue that is intentionally represented as true by the narrator.

In the case of The Pimlico Tapes, people feel that I am taking something true and deliberately representing it as untrue. Hah! I say to them, "Prove it."

The docudrama on television and sometimes in cinema has made good use of blurring the lines between fact and fiction. Imagine one of those political dramas featuring past or present senior politicians. References to certain events, phrases people use or they way they dress connect the characters to real life people or events. This is intentional of course but they don't say so officially. Certain elements in the drama are true but not all. Enough of them are true, however, that the viewer believes that all of what they are seeing might be true – or at least they do for a while. Such programs are often said to be fiction but based loosely upon real people and events. The question is, how loosely? Carefully, in most cases, they do not mention specific names. Some, on the other hand, do take the risk of mentioning names but it is a risk. It's a dangerous game and one that provides meat and drink for lawyers.

For myself, and perhaps for many others, the line between fact and fiction easily becomes blurred. I am a self-confessed fantasist. I live (as my father used to tell me) in a dream world. Many real things seem like fantasy to me and equally many unreal things seem painfully or pleasurably real. Step down all you therapists, I have no desire to be cured of this. I like my life this way, thanks. This does mean that often the things I invent (fictitious stories, or "lies" as I've chosen to call them), over time become fact to me. The more I read them, edit them and re-work them the more real they become. People pick me up on it.

"You're talking hypothetically of course," they say. Or "You mean if you had stolen the car!"

And I have to stop and think. Did I make it up? I'm not so sure I did. I remember everything about it – the place, the time, the people who were there, what shoes I was wearing, what I ate for breakfast that morning, the smell of the glovebox, the electric shock as I twisted the wires together. All of it. So it is real for me. Who's to say it didn't happen? Maybe in a different dimension, but it happened.

I wonder how that would stand up as prosecutory evidence in a court of law. By pure coincidence, I am a trained lawyer. Can you imagine how it would have been if I'd become a high-court judge? Outrageous. Yet there must be practicing judges out there who have the same tenuous grip on reality that I have. Fantasy Judge!

"I find you guilty because I met you in a dream once and you told me what you'd done." The mind certainly does boggle!

image courtesy of www.gizmodo.com

No comments:

Post a Comment